O N E E V E R Y O N E • Laura

O N E E V E R Y O N E • Laura

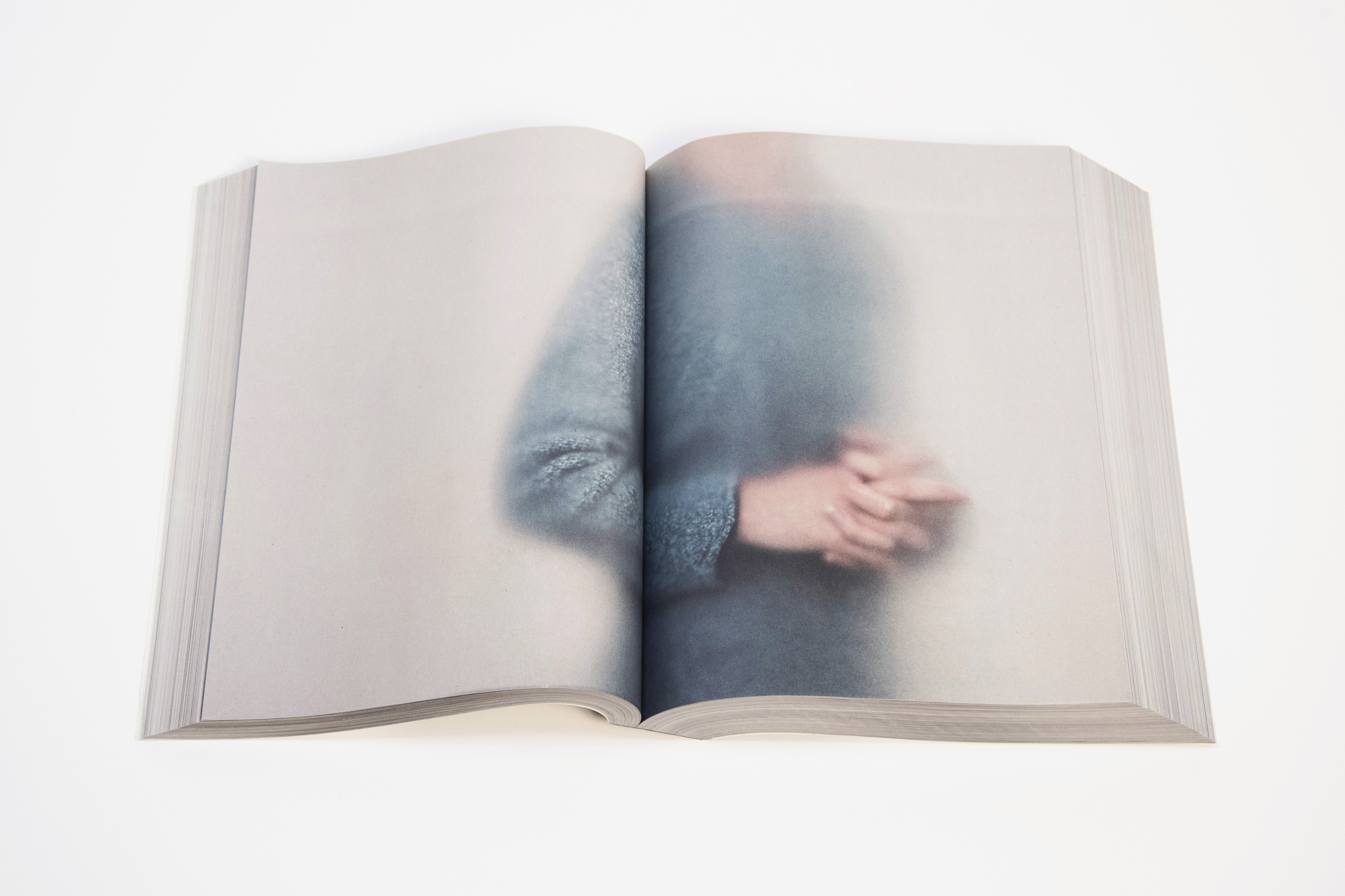

The O N E E V E R Y O N E series began when a chemist placed a skin-like film into my hand with a note: “I think you will find this interesting.” I did. Its soft rubber like membrane was thin but extremely tough. I was immediately captured by this paradox, as well as the optical quality of its milky surface rendering only what touches it—in this case, my fingertips—in focus while obscuring everything else. Experimenting with objects and hands near and far from its surface, I began to photograph through it. The way it makes touch visible seemed magic to me.

The thermoplastic polyurethane membrane, called Duraflex® and manufactured by Bayer MaterialScience LLC, is used to make bladders for holding large volumes of liquid under pressure (among other uses). I was partnered with Bayer MaterialScience in Factory Direct: Pittsburgh, The Warhol Museum’s 2012 project linking artists with Pittsburgh-based businesses. Bayer’s researchers initially introduced me to touch sensitive membranes and protective coatings for everything from hospital pads to cell phones, rain gear and surfboards; in fact, they are responsible for the feel of many surfaces we touch every day. Though the research campus is large and expands across several buildings, I was struck by the pervasive presence yet relative invisibility of their products. The distance between tactile experience and visual evidence is present in many of their materials and coatings. Contrast this with how Pittsburgh has been visually shaped by the structures and architectures of steel and heavy manufacturing. Somewhere between the invisibility of 21st century chemical processes and the visibility of 19th and 20th century mechanical production lies the newspaper, a physical vehicle for the conveyance of thought and experience. The project thus expanded to include The Pittsburgh Post Gazette, a locally owned newspaper.

With the Duraflex® suspended as a curtain, I worked on one side with my camera and an assistant. Employees at Bayer and at the Post Gazette stood on the other side of the membrane and held their hands and work-related objects up to the surface of the film: a pica ruler, a flexographic plate, a notebook, and a press gear from newspaper production; a test tube, a beaker, a syringe, a durometer from chemical production. Standing behind the semi-opaque film, one can hear but can not see, hidden until stepping toward the surface, guided by my voice. Each press of the object, the face, a hand, or cloth touching the membrane is revealed in focus, the shallow depth of field a consequence of the membrane’s optical qualities. The images made in this exchange—between a subject that offers self or object and a voice that stands in for the visually absent camera—record an interiority that is perhaps more private, more vulnerable than the self we offer up in the world of a constantly present camera. Following and trusting the voice while having a sense of being hidden makes a space for this vulnerability.

For Factory Direct, the Post Gazette printed the images as newspapers, an object produced and delivered in hand everyday. These newspapers were distributed at the exhibition and in a special edition to Pittsburgh households. Since then the project has continued to expand. In winter 2014, docents, volunteers, curators, and museum staff at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts were photographed holding works from the collection. For many it was a singular opportunity to physically touch an object selected for its emotional and intellectual connection but previously held only in the eye. Participants were also photographed empty handed, alone behind the membrane.

Watching how the membrane, its conditions of material and circumstance, seemed to transform people and reveal a more private self led to the expansion of the project in other venues. During the Art Dealers Association of America’s spring 2014 The Art Show in Park Avenue Armory, over 700 people were photographed through the Duraflex® over six days in the Carl Solway Gallery booth. The exchange continued by mail with everyone receiving a newsprint ephemera image of another participant. Selected images printed on tissue thin Japanese paper rustled in the air currents at the Transformer Station in Cleveland where they were exhibited later that year. Visitors to the common sense, a 2014-15 exhibition at the Henry Art Gallery in Seattle, were photographed as they entered or left the exhibit. Over 2,000 portraits were printed on newsprint and accumulated as dense wall hung pads while, in another gallery, visitors depleted and carried away newsprint images of animal feet and underbellies.

These project works, along with portraits of friends in the studio, are ongoing and have come to be called O N E E V E R Y O N E. Each image is a tactile register of an exchange. Experiencing the quality of these exchanges turned my interest toward working in a Public Health Context where what is ideally required of a every care giver is in the words of John Berger a fraternal relationship: “to recognize a patient with the certainty of an ideal brother. The function of fraternity is recognition.” Work with the Brown School of Social Work at Washington University in St. Louis and now with Landmarks and the Dell Medical School extends this project’s reach.

—Ann Hamilton

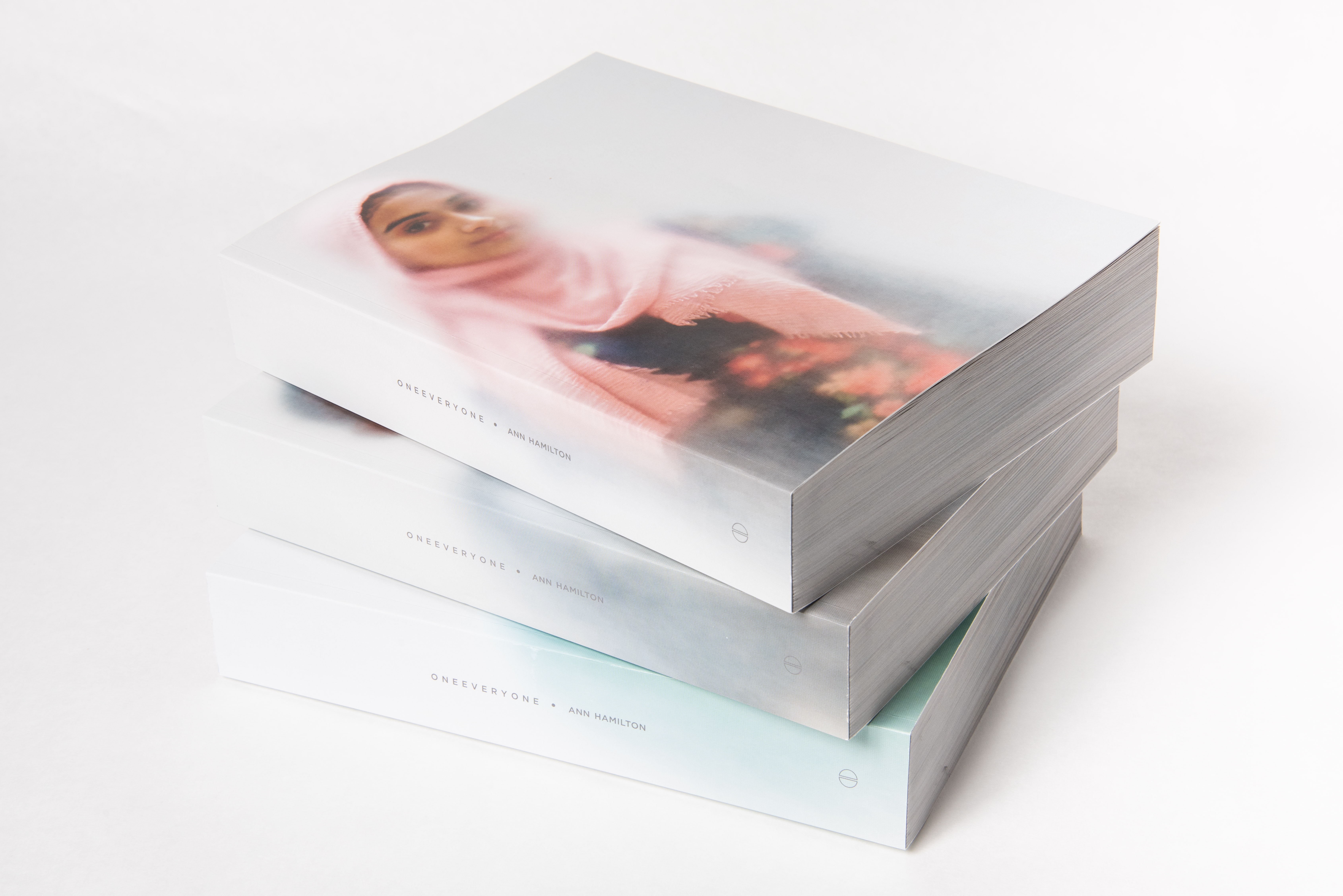

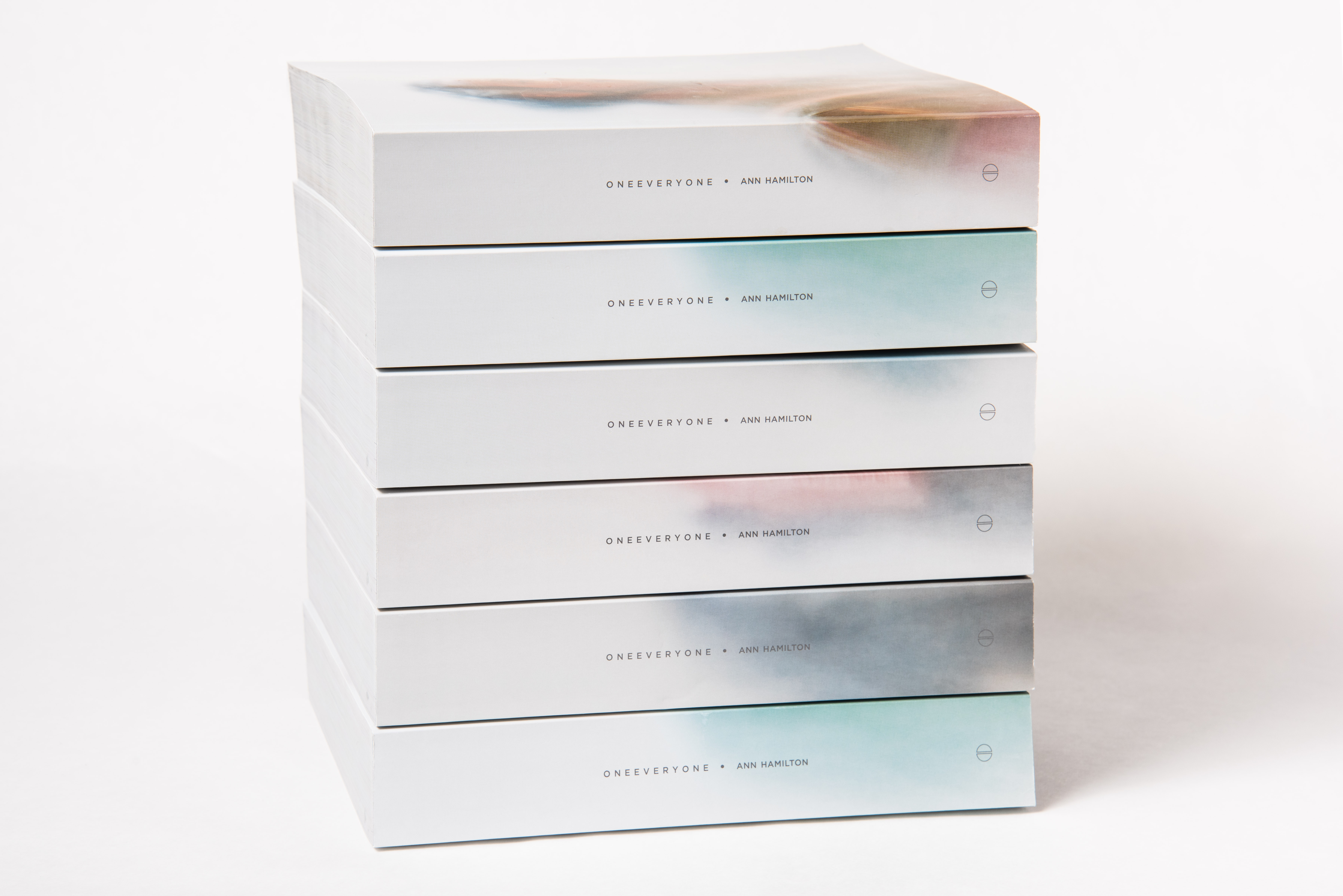

publication from O N E V E R Y O N E comissioned by Landmarks for the University of Texas at Austin

publication from O N E V E R Y O N E comissioned by Landmarks for the University of Texas at Austin

publication from O N E V E R Y O N E, Thompson Library and Wexner Center for the Arts at the Ohio State University

publication from O N E V E R Y O N E, Thompson Library and Wexner Center for the Arts at the Ohio State University